Rust Family Foundation: Archaeology Grants Program

Understanding Subsistence at Scale:

An Exploration of the Graeco-Roman Site of Al-Qarah al-Hamra in the Northeast Fayyum, Egypt

Principal Investigators:

Emily Cole, New York University/University of California, Berkeley

Bethany Simpson, University of California, Los Angeles

Archaeological excavation in the Fayyum region of Egypt has understandably focused on sites that have visible surface architecture and have yielded finds in an exceptional state of preservation. Less attention has been paid to the broad range of smaller villages, which no doubt proliferated throughout the countryside, owing to the continuous occupation of the region up to the present and poor levels of preservation within the cultivated Fayyum depression. Work by the Northeast Fayyum Lakeshore Project at the small settlement of Al-Qarah al-Hamra, under the direction of Dr. Emily Cole and Dr. Bethany Simpson, therefore provides an important opportunity to contribute to the understanding of the material culture of the ancient Fayyum at a hyper-local level.

Fig.1: Map of northern Egypt and the Fayyum region (Google Earth ver. 7.1.8.3036 (December 13, 2015). Egypt. 30°06'36.16" N 31°08'47.84" E, Elevation 601.24 km. inset: http://www.earth.google.com, accessed 20 May 2019 with the location of Al-Qarah al-Hamra.

The site of Al-Qarah al-Hamra occupies an area of roughly 1,300 sq. meters. In contrast, the visible surface remains at the nearby larger site of Karanis cover approximately 526,000 sq. meters. Even when the loss of architecture at Al-Qarah al-Hamra and the gradual expansion of Karanis are considered, Al-Qarah al-Hamra represents settlement on a significantly smaller scale (fig.1).

Previous Research at the Site

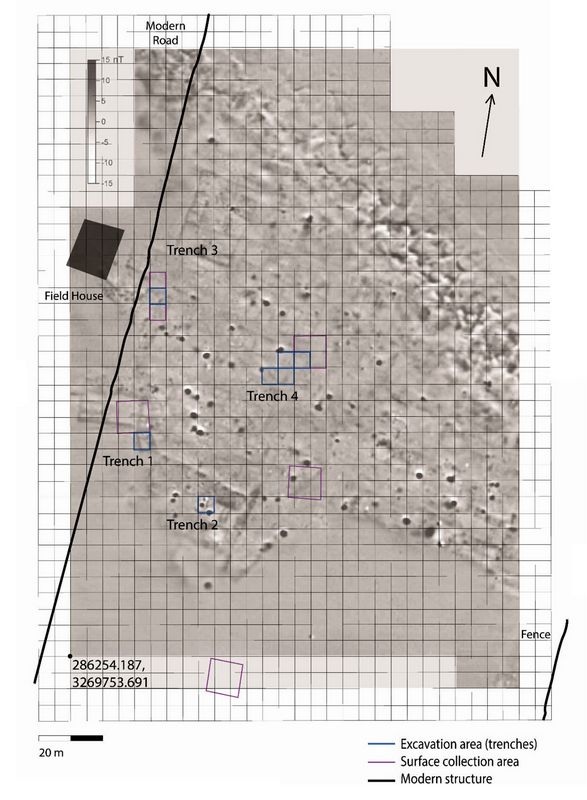

The site of Al-Qarah al-Hamra is located on the north shore of Lake Qarun on the outskirts of the Fayyum, in a semi-arid landscape (Fig.1). The site was excavated during two field seasons: in 2004 by a team from UCLA (Cappers et al. 2013, Barnard et al. 2015) and again in 2016, as part of the Northeast Fayyum

Lakeshore Project under the direction of

Dr. Emily Cole and Dr. Bethany Simpson. A magnetometric survey

conducted in 2004 by Tomasz Herbich revealed that the settlement

followed a well-defined orthogonal street plan, similar to most known

sites in the Fayyum (Herbich 2019). However, unlike some Fayyum

settlements, work at Al-Qarah al-Hamra has not revealed extensive

layers of overlapping structures, preliminarily suggesting a limited

time frame for occupation (fig.2).

Lakeshore Project under the direction of

Dr. Emily Cole and Dr. Bethany Simpson. A magnetometric survey

conducted in 2004 by Tomasz Herbich revealed that the settlement

followed a well-defined orthogonal street plan, similar to most known

sites in the Fayyum (Herbich 2019). However, unlike some Fayyum

settlements, work at Al-Qarah al-Hamra has not revealed extensive

layers of overlapping structures, preliminarily suggesting a limited

time frame for occupation (fig.2). Fig.2: Map of Al-Qarah al-Hamra with locations of 2004 and 2016 excavated trenches. Magnetometry map created by Tomasz Herbich. Southwest coordinate projected in WGS_1984_UTM_zone_36N, Transverse Mercator (© Northeast Fayyum Lakeshore Project).

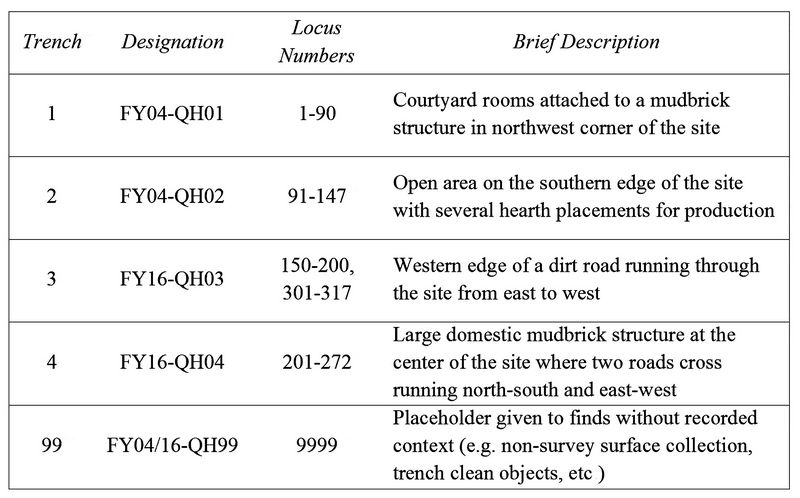

In 2004, Trenches 1 and 2 were excavated in order to test the site’s subsurface preservation (Table 1). Trench 1 consisted of three rooms in a courtyard area; excavated mudbrick walls corresponded to visible structures on the survey map. Based on the zooarchaeological remains, it is likely that this area was used for food-processing before transportati

on. Trench 2 included an area with dark features in the

magnetometric record, which happened to be a concentration of fire

activity. These hearth installations were likely used for some kind of

production on the southern edge of town, closest to the lake water and

downwind from the prevailing north wind.

on. Trench 2 included an area with dark features in the

magnetometric record, which happened to be a concentration of fire

activity. These hearth installations were likely used for some kind of

production on the southern edge of town, closest to the lake water and

downwind from the prevailing north wind. Table 1: Loci numbers assigned to excavated trenches at Al-Qarah al-Hamra.

To explore the structural development of the town, Trenches 3 and 4 were investigated in 2016. Trench 3 consisted of street deposits and the edge of the structures lining the throughway. Trench 4 exposed a large domestic building with an underground storage area on the southwest corner of two main streets, likely from the earliest phases of the settlement.

2017-2018 Funded Research Project (RFF-2017-21)

Goals:

Following the field seasons in 2004 and 2016, a study season was carried out in 2018 with the funding provided by the Rust Family Foundation. Though there are several goals for the project, the RFF funds were particularly aimed at the second (see below), namely the analysis of botanical and animal remains from Al-Qarah al-Hamra. By combining the results of these data, we have a more nuanced understanding of what was being consumed at the site, and in turn, we can address our third goal of integrating our results with existing knowledge of this region. The funded analyses were conducted by Frits Heinrich (Vrije Universiteit Brussel) in archaeobotany, Nami Shin (University of Tübingen) in anthracology, and Mauro Rizzetto (University of Sheffield) in zooarchaeology. The main goals are:

1. To reconstruct the foundation, development, and abandonment phases of the settlement of Al-Qarah al-Hamra

2. To investigate the agricultural practices, exploitation of wild species, and animal husbandry by the population living near the north shore of Lake Qarun

3. To help advance research relating to how small-scale settlements fit within a network of larger, established sites in the Fayyum region of Egypt

Methods: Archaeobotany

The archaeobotanical research focused on identifying the remains of different crops and wild taxa present at the site, whenever possible to the (sub)species level. Identification took place through the microscopic analysis of morphological features of both the desiccated and charred seeds and fruits that were encountered in the samples the specialist took. After an inventory was made, all soil samples were dry-sieved using a 0.5 mm sieve. The residues were subsequently ranked and the 37 samples which looked most promising in terms of their botanical content and/or were deemed of interest were selected for further processing.

Subsequently, some of the selected samples were wet-sieved using bucket flotation. Typically, flotation is not necessary in Egypt, but as some of the residues contained very high concentrations of gravel/very small stones as well as of lumps of clay, this was deemed necessary. In flotation, stones and sand sink to the bottom of the bucket while the charred or desiccated botanics, being less dense than water, float to the top. The water containing the light fraction of botanics was then carefully poured over a 0.5 mm sieve where they were collected. The buckets were stirred, and the process of pouring was repeated several times per sample to ensure all botanics were separated out. The botanical residue was then placed in very fine mash cloth bags, tied close, and hung to dry in on a washing line overnight. After drying, the samples were dry-sieved a final time over the 0.5 mm sieve to remove any remaining silt.

The botanics within the 37 samples were then sorted, identified and quantified using light stereo microscopes; all finds were registered on the sample recording forms as were any observations regarding the sample. Subsequently, finds were photographed using a DSLR camera with a magnifying lens; a photograph was taken of each taxon/plant part represented in the assemblage. Lastly, all botanics were (per taxon/plant part) placed in test tubes on which the taxon and plant part were recorded alongside the sample ID.

Methods: Anthracology

Charcoal or charred wood fragments from 2004 and 2016 were collected in the field by the excavators or from sieved botanical samples. Each sample was first scanned for pieces that were not charcoal and then sieved gently with a 2 mm metal geological sieve. Fragments under 2 mm in size cannot be properly identified. All samples were then weighed with a scale with a sensitivity of 0.01 g. The samples contained limited amounts of charcoal, so every piece of charcoal was analyzed. A stereo microscope with a magnification ranging from 6-7x was used to identify fragments by cross section. In cases where the radial and tangential sections of a fragment needed to be seen, a modified transmission light microscope with a magnification up to 400x was used. Unless the fragment could be identified without a clean break, most fragments were broken to reveal a clean cross section.

Methods: Zooarchaeology

The faunal material from Al-Qarah al-Hamra was recovered using a 2 mm mesh size sieve. The recording protocols adopted followed a selective approach in the material to be recorded, which aimed to minimise taphonomic biases (Maccarinelli 2018; Rizzetto 2019; Maccarinelli and Stocco forth.). Identification relied on comparisons with modern specimens from the Northeast Fayyum Lakeshore Project reference collection, as well as on a series of mammal, bird, and fish bone atlases (e.g. Barone 1976; Gayet and Van Neer 1990; Radu 2005). Low-level taxonomic identification of fish remains was hindered by anatomical similarities between closely related taxa, as well as by inevitable limitations in the available reference collection; in many cases, fish remains could only be identified to family- or order-level. For this reason, although all identified taxa are mentioned, the quantitative analyses of fish remains focused on the relative proportions of catfish and perciforms. This solution has several advantages. It provided a simplified but clear visualisation of taxonomic frequencies in the assemblage and in the different trenches; it also allowed to investigate body part representation and biometrical differences on large-enough samples to draw reliable interpretations on fish exploitation at the site.

Quantification relied on the distinction between countable and non-countable fragments. Countable fragments consist of a selected set of diagnostic zones that are the same for all taxa. For example, even small fragments from catfish neurocrania could be easily identified and assigned to this taxon, but the same is not true for other fish taxa. Therefore, these and other elements were excluded from quantification analyses, as they would have led to an overrepresentation of catfish and, in particular, of the cranial elements of this taxon.

NISP (Number of Identified Specimens) frequencies rely on raw counts of countable elements. The MNI (Minimum Number of Individuals) calculates, for each taxon and within each excavation unit, the minimum number of individuals necessary to account for the number of fragments recorded. This is obtained by calculating the MNE (Minimum Number of Elements; in turn, this is the minimum number of elements necessary to account for the number of recorded fragments of that element) for each element, and adjusting it by the number of those elements in the fish skeleton; for each taxon, the highest adjusted MNE (called MAU, Minimum Number of Anatomical Units) equals to the MNI (Grayson 1984; Lyman 2008). In this study, the MNIs of catfish and perciforms calculated for each trench were the sum of MNIs from each locus within that trench. Measurements on fish bones were taken according to Morales-Muñiz and Rosenlund (1979), and Van Neer and Lesur (2004).

Observations and Results: Archaeobotany

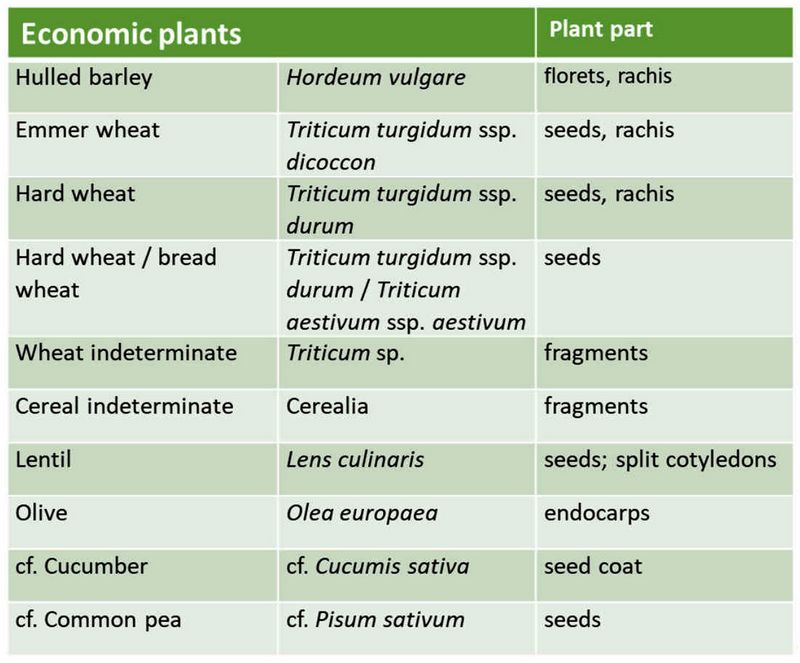

Two general observations can be made with regards to the Al-Qarah al-Hamra botanical materials: 1) the grand majority of the material was preserved in a carbonized/charred state, and 2) the carbonized/charred material overall had a poor quality in terms of preservation. Due to its dry conditions, desiccated preservation

of plant materials is

common and typically dominant in Egypt. A good example is nearby

Karanis. In order to survive, desiccated material requires permanent

dry conditions: if the material is rehydrated it will start to

germinate or decompose as plant materials are wont to do. Charred

materials can no longer rot: they are therefore not affected by water.

Therefore, charred archaeobotanical materials are most commonly found

worldwide.

of plant materials is

common and typically dominant in Egypt. A good example is nearby

Karanis. In order to survive, desiccated material requires permanent

dry conditions: if the material is rehydrated it will start to

germinate or decompose as plant materials are wont to do. Charred

materials can no longer rot: they are therefore not affected by water.

Therefore, charred archaeobotanical materials are most commonly found

worldwide.Table 2: Economic plant remains encountered in analyzed samples (F.B.J. Heinrich).

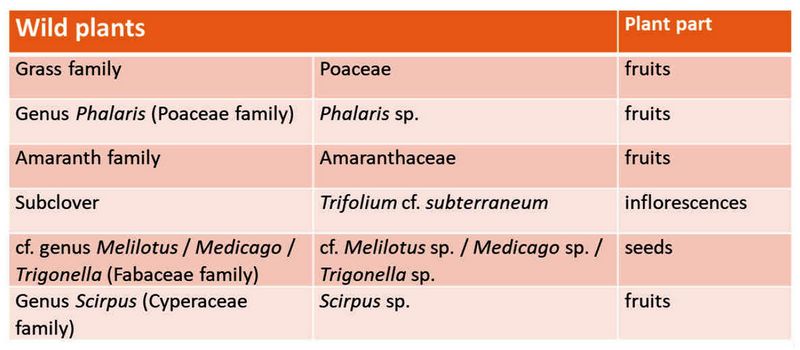

The almost complete absence of desiccated materials, in combination with the finds of charred materials throughout the samples, suggests that the samples were exposed to moisture. The moisture may have originated from the groundwater (if the ground water table was high), or from flooding. For Al-Qarah al-Hamra, (repeated) flooding during Late Antiquity has been forwarded as a hypothesis (B

arnard et al. 2015). The

preservation state of the botanical material would support this

hypothesis.

arnard et al. 2015). The

preservation state of the botanical material would support this

hypothesis. Table 3: Wild plant remains encountered in analyzed samples (F.B.J. Heinrich).

Many highly fragmented cereal remains, often badly damaged during carbonization, were encountered (Tables 2 and 3). Sometimes these could be identified to the genus level (Triticum sp.), or to the (sub)species, yet sometimes it could only be concluded they represent cultivated cereal remains (‘Cerealia’). In addition, some possible fragments of carbonized food remains (possibly bread) where encountered in which cereal material, clearly barley, was visible. Further comparisons will be necessary to exclude the possibility of the material representing carbonized dung.

Observations and Results: Anthracology

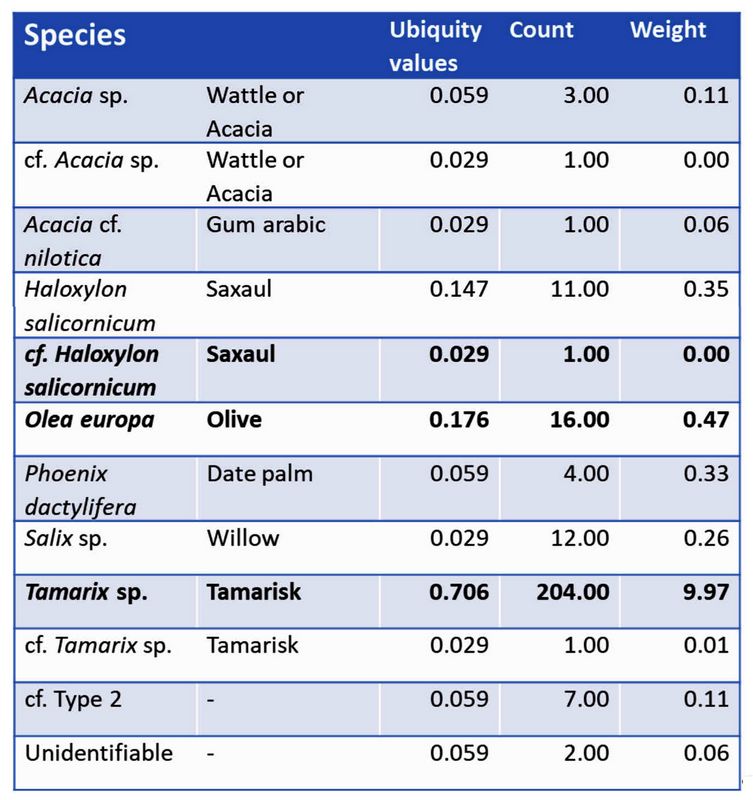

All of the wood taxa identified at Al-Qarah al-Hamra were also found at nearby Karanis and are “local” taxa, either endemic or naturalized through

extended cultivation (Table 4). Based on ubiquity tamarisk

(Tamarix sp.) and olive (Olea europaea) seem to have been the most

commonly used woods at the site and were most likely specified for

practical use such as fuel burning. The reason being charred dung

remains are not found at the site and while this does not exclude the

use of dung as fuel, the distribution of remains across the site and

the either endemic or naturalized nature of the tree taxa suggest that

wood was not a scarce resource.

extended cultivation (Table 4). Based on ubiquity tamarisk

(Tamarix sp.) and olive (Olea europaea) seem to have been the most

commonly used woods at the site and were most likely specified for

practical use such as fuel burning. The reason being charred dung

remains are not found at the site and while this does not exclude the

use of dung as fuel, the distribution of remains across the site and

the either endemic or naturalized nature of the tree taxa suggest that

wood was not a scarce resource. Table 4: Wood taxa encountered in analyzed samples (N. Shin).

At the present moment it is not possible to see if there was wood-taxa discrimination for special wood items (toys, figurines, utensils, etc) versus fuel-wood. Yet, the contexts where the charcoal remains were found were most likely secondary or even tertiary deposits and thus the charcoal remains found in these types of deposits may represent activities related to burned trash-disposal and/or refuse related to other domestic activities such as cooking. Thus, the samples are more likely to reveal the types of woods favored for more common daily activities rather than special events or items.

Though there were only thirty-four total samples, the trenches seem to exhibit some differences in the present taxa. Tamarisk is found in all four trenches indicating that it had widespread use at Al-Qarah al-Hamra, again suggesting the taxon’s high availability. In contrast, 100% of the saxaul (Haloxylon sp.) found at Al-Qarah al-Hamra is found only in Trench 3. Owing to being found in midden deposits in this trench, it may have been used specifically by those in the adjacent structures as fuel. The concentration of saxaul in Trench 3 may, however, also represent a single event and not a special pattern of use of the taxon in that space. This will only be confirmed with continued excavation and a larger number of samples.

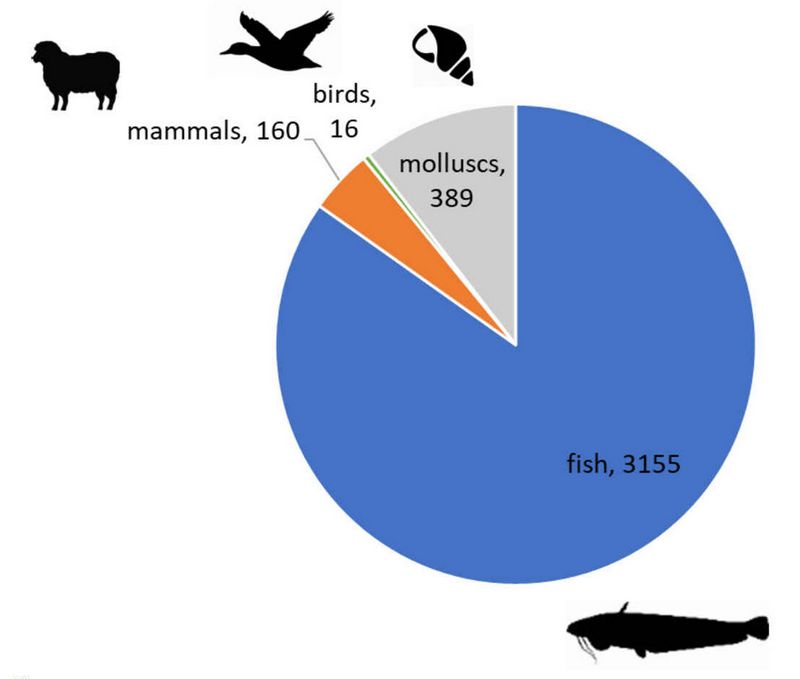

Observations and Results: Zooarchaeology

Mammal and bird remains were rare in the assemblage, with only 176 recorded fragments (Fig. 3). Remains from domestic mammal species include bone and tooth fragments of cattle (Bos taurus), caprine (

sheep/goat, Caprinae), and equids (horse/donkey/hybrids, Equidae), while suids

(pig/wild boar, Sus sp.) were absent; dog (Canis familiaris) was

present with a complete skeleton from Trench 1. No certain remains from

wild mammals were identified. Thirteen bone fragments of anatids

(Anatidae), most likely mature ducks, were identified, eleven of which

were from Trench 1.

sheep/goat, Caprinae), and equids (horse/donkey/hybrids, Equidae), while suids

(pig/wild boar, Sus sp.) were absent; dog (Canis familiaris) was

present with a complete skeleton from Trench 1. No certain remains from

wild mammals were identified. Thirteen bone fragments of anatids

(Anatidae), most likely mature ducks, were identified, eleven of which

were from Trench 1.Fig.3: General taxonomic frequencies in analyzed samples (M. Rizzetto).

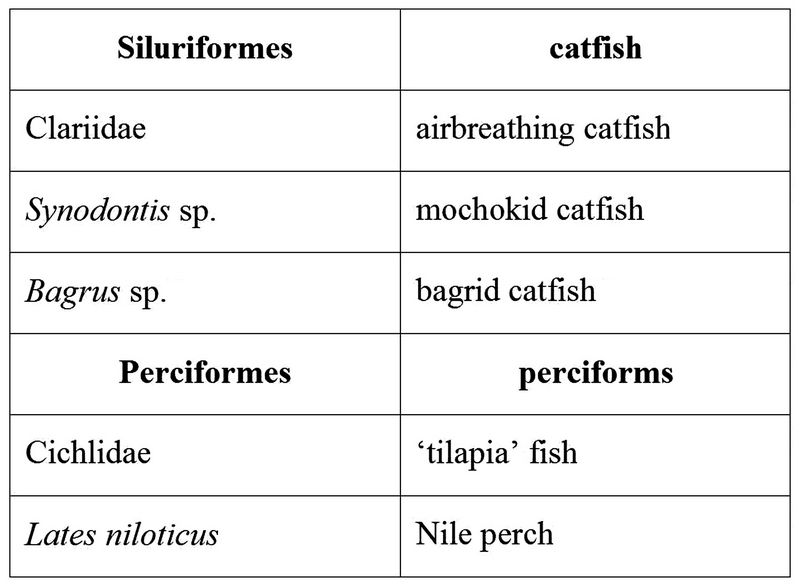

In total, 3,155 fish bone fragments were recorded, with 964 identified at least to order-level (Table 5). Only freshwater taxa were present. Among Siluriformes

(catfish), species from the families Clariidae

(Clarias sp. and/or Heterobranchus sp., airbreathing catfish),

Mochokidae (Synodontis sp., mochokid catfish), and Bagridae (Bagrus

bajad and/or Bagrus docmak, bagrid catfish) were represented, although

the vast majority of catfish remains most likely belong to the clariid

family (ca. 80%).

(catfish), species from the families Clariidae

(Clarias sp. and/or Heterobranchus sp., airbreathing catfish),

Mochokidae (Synodontis sp., mochokid catfish), and Bagridae (Bagrus

bajad and/or Bagrus docmak, bagrid catfish) were represented, although

the vast majority of catfish remains most likely belong to the clariid

family (ca. 80%). Table 5: Fish taxa encountered in analyzed samples (M. Rizzetto).

For Perciformes, species from the families Cichlidae (e.g. ‘tilapia’ species such as Oreochromis niloticus, Nile tilapia, and Oreochromis aureus, blue tilapia) and Latidae (Lates niloticus, Nile perch) were present. The countable elements in the assemblage were 644, and these have been used in the quantification analyses below.

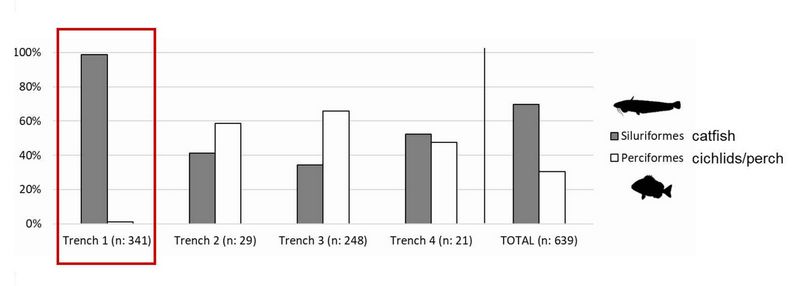

Fig.4: Frequencies of fish by trench. Catfish prevail at the site in general, though with spatial differences (M. Rizzetto).

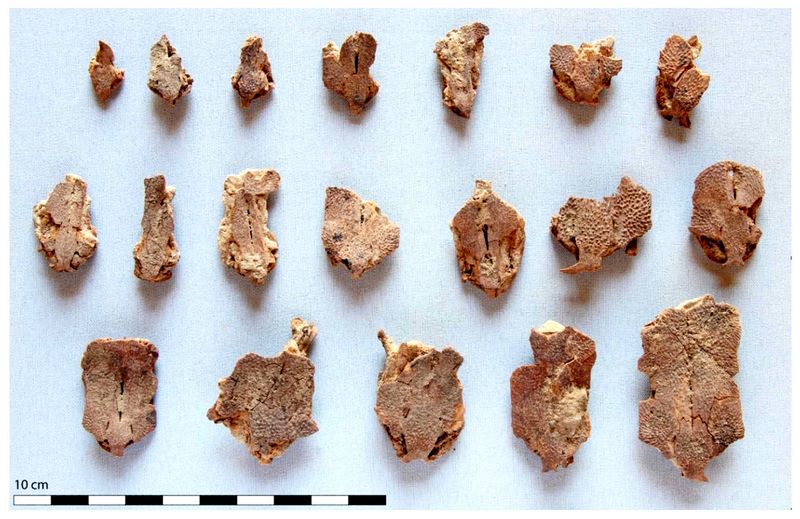

Direct evidence for butchery was limited to four chop marks, all detected on fish head bones from Trench 1. Three (one cleithrum and two fragments from the neurocranium) belonged to catfish, and one (a cleithrum) to a cichlid. The high incidence of isolated catfish crania (Fig. 5), held in articulation by salt concretions and mostly recovered together from Locus 30, suggests that, at least for this taxon, the head was often removed during butchery. The incidence of catfish cranial elements relative to vertebrae was much higher in Trench 1 than in the other trenches. Biometrical analyses suggest the catfish introduced to Trench 1 was on average smaller than in other parts of the site.

Fig.5: Cranial catfish elements from Trench 1, Locus 30 (n: 137). Generally, more cranial elements were identified for catfish. Trench 1, however, had a larger relative number of cranial elements (>80% with n: 337 in Trench 1, compared with >50% with n: 85 in Trench 3) (© Northeast Fayyum Lakeshore Project).

Conclusions:

The small settlement of Al-Qarah al-Hamra reveals analogous material and architectural repertoires to larger sites in the Fayyum, attesting to the extent of continuity in material culture in the region, even at a more remote location at the desert edge. The connection between Al-Qarah al-Hamra and areas outside of the Fayyum is also significant; ceramic analysis attests to connections with Delta sites—either directly or by means of trade through larger Fayyum sites—as well as a possible network with Upper Egypt and the Western Oases (Ringheim 2019). The ceramics indicate occupation from at least the second century BCE, though possibly earlier in the late third century BCE. There is currently little evidence for pottery dating later than the Early Roman period, suggesting a substantial abandonment of the site by the end of the 2nd century CE.

With regards to the zoological and botanical materials, however, the data point to a local adaptation of subsistence practices at Al-Qarah al-Hamra. Preliminary assessment of the botanical remains suggests small-scale agriculture between the lake shore and the edge of the desert. Despite the often recognized crop shift from emmer wheat to hard wheat during the Graeco-Roman periods (for a historiography, see Heinrich 2017, cf. Heinrich 2019), emmer wheat is still present at Al-Qarah al-Hamra. This is confounding as this shift in crop selection is typically believed to have been brought about by the Hellenistic settlers. While a gradual shift (on gradual crop shifts, see also Heinrich and Hansen forth.), with both crops remaining important side by side for a while, can be conceived of at previously existing settlements, it is harder to explain for new strongly Hellenized foundations in the Fayyum and may require us to adapt this hypothesis. Perchance this shift set in later, was far more gradual than previously assumed, or most interestingly, may have been motivated by different circumstances and causes than Hellenization alone. Further investigation and excavation of a likely granary detected in the 2004 magnetometric survey of the site will no doubt further elucidate these results.

The dearth of mammal and bird remains in the faunal assemblage from Trenches 1-4 is, moreover, remarkable and may be explained by a preference for specific animal products, waste disposal practices, or the excavation of a limited area of the site. If the material so far recovered, however, is representative of animal exploitation strategies at the site, it is possible to assume that the inhabitants of Al-Qarah al-Hamra relied largely on fishing as a source of animal proteins, complemented by water fowling along the lakeshore and the very occasional consumption of products from domestic mammals and mollusks. The complete lack of suids in particular would contrast sharply with the abundance of pig remains from nearby Karanis and may be the result of different microenvironmental conditions (Linseele et al. 2013).

The fish assemblage was largely dominated by catfish (mainly represented by clariid species), followed by cichlid fish. Such predominance of catfish is not uncommon and likely reflects the natural abundance of this taxon, as well as its value as a source of food. A high proportion of catfish remains has been attested at other Graeco-Roman sites in the Nile basin, including Karanis in the Fayyum (Linseele et al. 2013).

The intra-site differences in the incidence of cranial elements at Al-Qarah al-Hamra are likely the result of human activities, whereby the head of the fish was removed and discarded onsite (Trench 1), with the rest of the body being moved elsewhere. Although most of the archaeological evidence indicates that catfish was usually cured whole (as is still done for smoked catfish nowadays) (Van Neer 2004 and references therein), it is tempting to interpret this evidence as the result of fish curing, which would have taken p

lace in the Trench 1 area and

focused on catfish. The smaller size of catfish from Trench 1 might

reflect deliberate choices on the type of fish required for curing.

lace in the Trench 1 area and

focused on catfish. The smaller size of catfish from Trench 1 might

reflect deliberate choices on the type of fish required for curing.Fig.6: View of Trench 1, Locus 30, a collection of debris and the mudbricks from a basin. A small hearth structure was located beneath the amphora at the left of this image (© Northeast Fayyum Lakeshore Project).

The groups of articulated fish heads from Trench 1 were found together in Locus 30, a trash deposit directly above the compact mud-floor surface of a room with two hearth installations and a mudbrick basin structure (fig 6). These features possibly suggest a scale of activities beyond ordinary household consumption; the location of the building itself, on the south-western corner of the settlement and closer to the lake, also fits well with an interest in placing the malodorous nature of fish processing at the edge of the village.

Fig.7:

View of Trench 4, with remains of a domestic structure. Lack of visible

surface remains owing to submersion does not affect the mudbrick

architecture remains beneath the surface (© Northeast Fayyum Lakeshore

Project).

Fig.7:

View of Trench 4, with remains of a domestic structure. Lack of visible

surface remains owing to submersion does not affect the mudbrick

architecture remains beneath the surface (© Northeast Fayyum Lakeshore

Project).The predominant north wind of the Fayyum further supports the placement of industries, such as fish processing and ceramics firing, on the southern edge of sites throughout the region. Furthermore, this trench produced almost 85% of the instances of water fowl remains thus far discovered at Al-Qarah al-Hamra. With all of these results, however, further research is needed to provide a full picture of the agricultural and animal husbandry practices at the site.

Overall, high levels of calcification on surface ceramics as well as the complete lack of architectural remains above the sand at Al-Qarah al-Hamra (fig.7) indicate that the site was submerged beneath Lake Qarun for some length of time (fig.8). Botanical remains support this assessment, as extended periods of submersion would explain the lack of desiccate

d remains at the site. Further excavation and geological

survey will be carried out to establish when this submersion event (or

series of events) took place.

d remains at the site. Further excavation and geological

survey will be carried out to establish when this submersion event (or

series of events) took place. Fig.8: View across the site of Al-Qarah al-Hamra (ca. -40 m asl) looking to the South with Lake Qarun (currently ca. -44 m asl) visible on the horizon (© Northeast Fayyum Lakeshore Project).

These investigations are crucial in light of the ongoing expansion of agriculture in the area near the desert sites and the accompanying rise in ground water that threatens the archaeological remains. Our new avenues of research will add further information to our understanding of the local use of water resources, the environmental changes in antiquity, and the connections formed between different sized settlements in the region

Acknowledgements:

The work at Al-Qarah al-Hamra took place with the kind permission and cooperation of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities. The Northeast Fayyum Lakeshore Project would like to thank our inspectors, Ashraf Sobhy Rezk Alla (2004), Rania Moustafa (2016), and Yasser Youssef Abdul Sattar (2018), as well as other members of the Ministry of Antiquities in Cairo and the Fayyum for their support.

References:

Barone, R. 1976. Anatomie Comparée Des Animaux Domestiques: Ostéologie. Paris: Vigot Frères.

Bernard, H., W. Wendrich, B. Nigra, B. Simpson, and R. Cappers. 2015. “The Fourth-Century AD Expansion of the Graeco-Roman Settlement of Karanis (Kom Aushim) in the Northern Fayum.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 101: 51-67.

Cappers, R., E. Cole, D. Jones, S. Holdaway, and W. Wendrich. 2013. “The Fayyum Desert as an Agricultural Landscape: Recent Research Results.” In C. Arlt and M. Stadler (eds.), Das Fayyum In Hellenismus und Kaiserzeit: Fallstudien zu multikulturellem Leben in der Antike, 35-50. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Gayet, M., and W. Van Neer. 1990. “Caractères Diagnostiques Des Épines De Quelques Silures Africains.” Journal of African Zoology 104: 241-52.

Grayson, D. K. 1984. Quantitative Zooarchaeology. Orlando: Academic Press.

Heinrich, F. B. J. 2017. “Modelling crop-selection in Roman Italy. The economics of agricultural decision making in a globalizing economy.” In T.C.A. de Haas and G.W. Tol (eds.), The economic integration of Roman Italy. Rural communities in a globalizing world, 141-169. Leiden: Brill.

Heinrich, F. B. J. 2019. “Cereals and Bread” in: P. Erdkamp & C. Holleran (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Diet and Nutrition in the Roman World, 101-115. London: Routledge.

Heinrich, F. B. J. and A. M. Hansen. Forthcoming. “Mud bricks, cereals and the agricultural economy. Archaeobotanical investigations at the New Kingdom Town” in J. Budka (ed.) Across Borders 2: Living in New Kingdom Sai. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press.

Herbich, T. 2019. “Efficiency of the magnetic method in surveying desert sites in Egypt and Sudan: Case studies.” In Raffaele Persico et al. (eds.), Innovation in Near-Surface Geophysics: Instrumentation, Application, and Data Processing Methods, 195-251. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Linseele, V., W. Van Neer and W. Wendrich. 2013. “Animals at the Graeco-Roman town of Karanis (Fayum Oasis, Egypt).” Conference poster presented at the 11th meeting of the ICAZ Archaeozoology of South-West Asia and adjacent areas (ASWA) Working Group, Haifa, 23rd-28th June 2013.

Lyman, R. L. 2008. Quantitative Palaeozoology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maccarinelli, A. 2018. The Social and Economic Role of Freshwater Fish in Medieval England: A Zooarchaeological Approach. Master’s Thesis, University of Sheffield.

Maccarinelli, A. and M. Stocco. Forthcoming. "A New Approach to Rationalizing Archaeological Shells."

Morales-Muñiz, A., and K. Rosenlund. 1979. Fish Bone Measurements. An Attempt to Standardize the Measurement of Fish Bones from Archaeological Sites. Copenhagen: Steenstrupia.

Radu, V. 2005. Atlas for the Identification of Bony Fish Bones from Archaeological Sites. Bucharest: Contrast.

Ringheim, H. 2019. “Mediterranean Influence in the Ceramic Assemblage of the Small-scale Settlement of Al-Qarah al-Hamra.” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 23: 78-99.

Rizzetto, M. 2019. Developments in Animal Husbandry between the Late Roman Period and the Early Middle Ages: A Comparative Study of the Evidence from Britain and the Lower Rhineland. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield.

Van Neer, W. 2004. Evolution of prehistoric fishing in the Nile Valley. Journal of African Archaeology 2(2): 251-269.

Van Neer, W., and J. Lesur. 2004. “The Ancient Fish Fauna from Asa Koma (Djibouti) and Modern Osteometric Data on Three Tilapiini and Two Clarias Catfish Species.” Documenta Archaeobiologiae 2: 141-60.

.

Recent Foundation grants: general Archaeology Grants Program w/map

Copyright © 2020 Rust Family Foundation