Rust Family Foundation: Archaeology Grants Program

Excavations on the Kephali Hill at Sissi (Crete)

Principal Investigator: Jan Driessen

Professor, University of Louvain

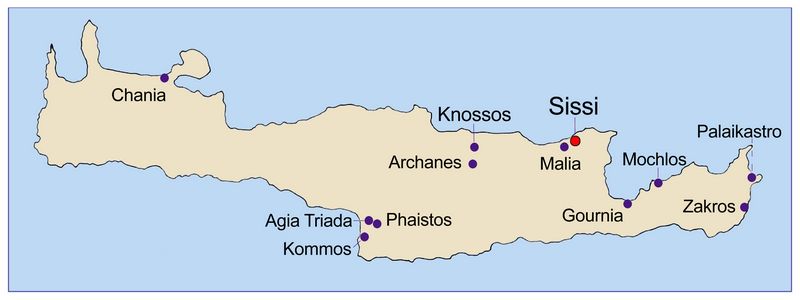

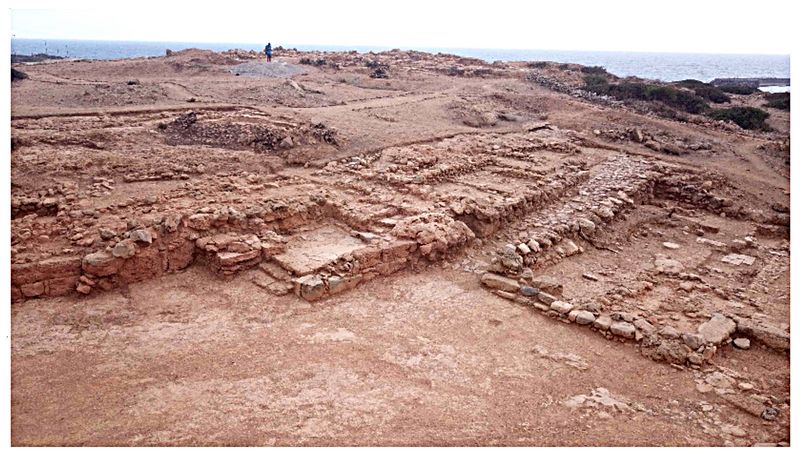

The Minoan Settlement on the Kephali hill at Sissi occupied a strategic location in Bronze Age Crete. Less than 4 km east of the major palace center at Malia on the north shores of the Greek island, the site lay on the coastal hill of Kephali tou Agiou Antoniou, locally known as Bouffo (figs. 1-3). With a beach on both si

des

– ideal anchorage places – the Kephali lies at the outlet of the river

flowing down the Selinari gorge, which is exactly opposite the hill.

des

– ideal anchorage places – the Kephali lies at the outlet of the river

flowing down the Selinari gorge, which is exactly opposite the hill. Fig.1: Map of Crete showing the location of Sissi and other sites.

Then and now this gorge formed the only overland access from Central to East Crete. This strategic position was undoubtedly the reason why the Kephali attracted the attention of early settlers and from its initial foundation around 2600 BCE, it remained occupied until the end of the Bronze Age, around 1200 BCE.

During its early history, the Kephali was apparently only one out of a series of small hamlets, which dotted the coast of the larger Malia bay but soon it would outgrow its neighbors and become the second settlement in the region after Malia.

During the Early and Middle Bronze Age (c. 2600-1750 BCE), the deceased of the settlement on the summit of the hill were buried in an adjoining cemetery at the north foot of the hill, close to the sea. Here, small house-like tombs were constructed at various moments, which allow us to follow the evolution of burial rites up to the sudden abandonment of the cemetery in the 18th c BCE. This abandonment coincides with the destruction of the First Palaces on the island, including the violent devastation of nearby Malia. Sissi too seems to have suffered.

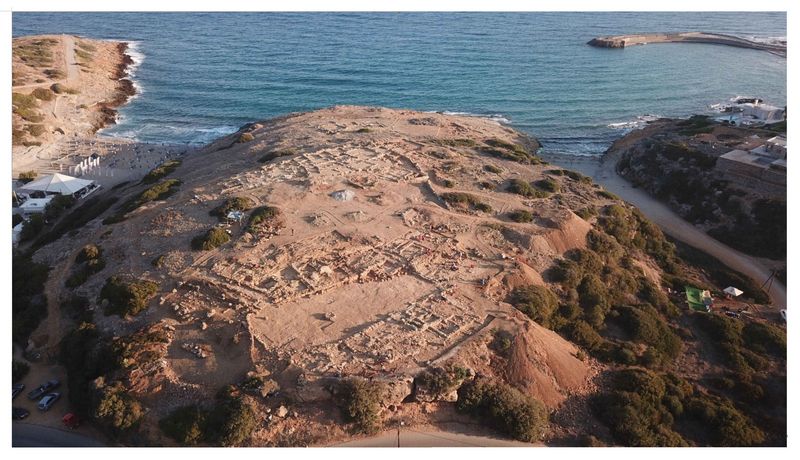

Fig.2: Aerial photograph of the site of Sissi on the hill of Kaphali (2018). (The rights of the monuments depicted belong to the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports [Law 3028/2002] © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports).

The picture is still somewhat hazy for the following period, Middle Minoan III, but recent work suggests that the Kephali-settlement at Sissi steered a more independent course. The clearest indications for this are the construction of a solid fortification wall at the foot of the hill and especially the installation of a large court-centered complex on a lower terrace of the summit, intentionally incorporating earlier remains in its construction.

Excavation of this court-centered building is ongoing but its central court was completed during the summer of 2018, thanks to the grant of the Rust Family Foundation. This court could host larger crowds for festivals and religious meetings, as indicated by several ritual installations that have been found.

At, or around, the time of the Santorini eruption, conventionally dated around 1530 BCE, however, this ceremonial complex was suddenly abandoned while the rest of the settlement continued.

Two or three generations later, the remaining settlement at Sissi, as so many other Minoan settlements and palace centers on Crete, was destroyed by fire and the nature of occupation drastically changes. After 1450 BCE, the ruins of earlier buildings on the summit of the hill were partly incorporated, partly overbuilt by a large architectural complex that betrays influences of the Mycenaean Mainland. It now includes various bi-columnar halls with central hearths, axially accessible, reflecting an architectural type that is also attested at Malia, Gournia and Plati on Crete and perhaps housing the local representative of the central administration of the palace at Knossos.

Within the Sissi

complex there is also a small snake-tube shrine and various storage and

artisanal areas. During its advanced Late Bronze Age occupation (around

1280 BCE), the complex suffered from an earthquake destruction

accompanied by fire after which it needed rebuilding. Oddly enough,

late in the 13th c. BCE, this complex and the rest of the site were

suddenly abandoned. Fortunately, apart from metal, all other objects

were left in place, allowing a proper reconstruction of its internal functioning.

Within the Sissi

complex there is also a small snake-tube shrine and various storage and

artisanal areas. During its advanced Late Bronze Age occupation (around

1280 BCE), the complex suffered from an earthquake destruction

accompanied by fire after which it needed rebuilding. Oddly enough,

late in the 13th c. BCE, this complex and the rest of the site were

suddenly abandoned. Fortunately, apart from metal, all other objects

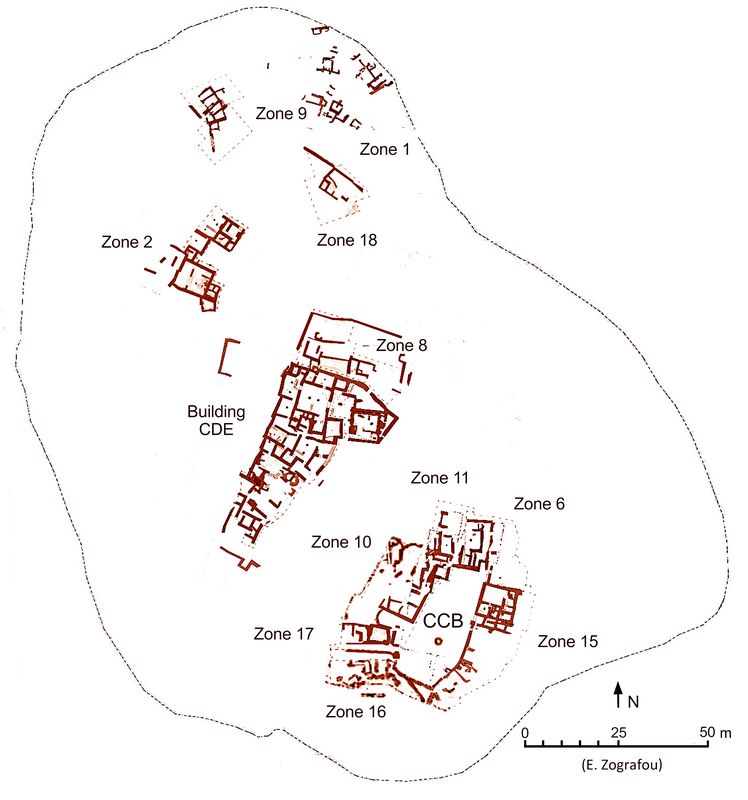

were left in place, allowing a proper reconstruction of its internal functioning. Fig.3: Site plan (2018) of the Minoan Settlement at Sissi. The Court-Centered Building (CCB) is at bottom (after E. Zografou).

Previous Work at the site:

Survey and excavation of the Minoan site at the Kephali hill have been conducted from 2007 onwards by a team of the University of Louvain under the auspices of the Belgian School at Athens. These past excavations, five 6-weeks campaigns between 2007 and 2011 and four between 2015 and 2018, led to the publication of four preliminary reports (Sissi I-IV) and a series of scientific lectures and articles (cf. our updated website www.sarpedon.be). A second 5-year excavation program has started in 2015 and will be achieved in 2019 after which study campaigns will follow. A fifth preliminary report on the excavations of the 2017-2018 campaigns is in preparation.

2018 Funded Research Project (RFF-2017-59)

Fig.4: Drone view of the Kephali Hill at Sissi from the Southeast after the

2018 campaign. The Ceremonial building’s court can be

distinguished in the center (photo: N. Kress. The

rights of the monuments depicted belong to the Hellenic Ministry of

Culture and Sports [Law 3028/2002] © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and

Sports).

Fig.4: Drone view of the Kephali Hill at Sissi from the Southeast after the

2018 campaign. The Ceremonial building’s court can be

distinguished in the center (photo: N. Kress. The

rights of the monuments depicted belong to the Hellenic Ministry of

Culture and Sports [Law 3028/2002] © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and

Sports).Goals:

The principal aim of the Sissi project is a detailed exploration of the settlement and cemetery on the Kephali in order to compare it with that of nearby Malia. Because of a similar diachronic occupation, the site presents an ideal case study to explore the relationships through time between a first-order center (= Malia) – where a palace would be built from Middle Minoan I or the 20th c. BCE onwards (if not earlier) – and a secondary site in its immediate hinterland. Both sites remained in use until their final abandonment in the late 13th c. BCE. This provides an interesting test case to compare intra-regional material culture – both where production and consumption are concerned – and opens interesting research avenues to explore various forms of dependency through time and the implementation of emerging social and economic links. The discovery of a court-centered complex – confirmed by the 2015-2018 excavations – has added unsuspected angles of research and interpretation to this comparative study.

Methodology:

In practice, excavation on the Kephali is by hand, involving mainly experienced local personnel and accomplished archaeologists, assisted by students from many nationalities, giving our project the appearance of a field school. We aim at full recovery through dry and water sieving, following strict sampling protocols that have been developed by the relevant specialists. This especially applies to environmental data (fauna, flora, shells, etc.). In addition, 100 g sediment samples for phytolith analysis are selected from each adequate sedimental unit and all excavation is accompanied by a full geomorphological study on site formation processes, including through micromorphologi

cal sampling

and FTR analysis. We also pay much attention to residue analysis.

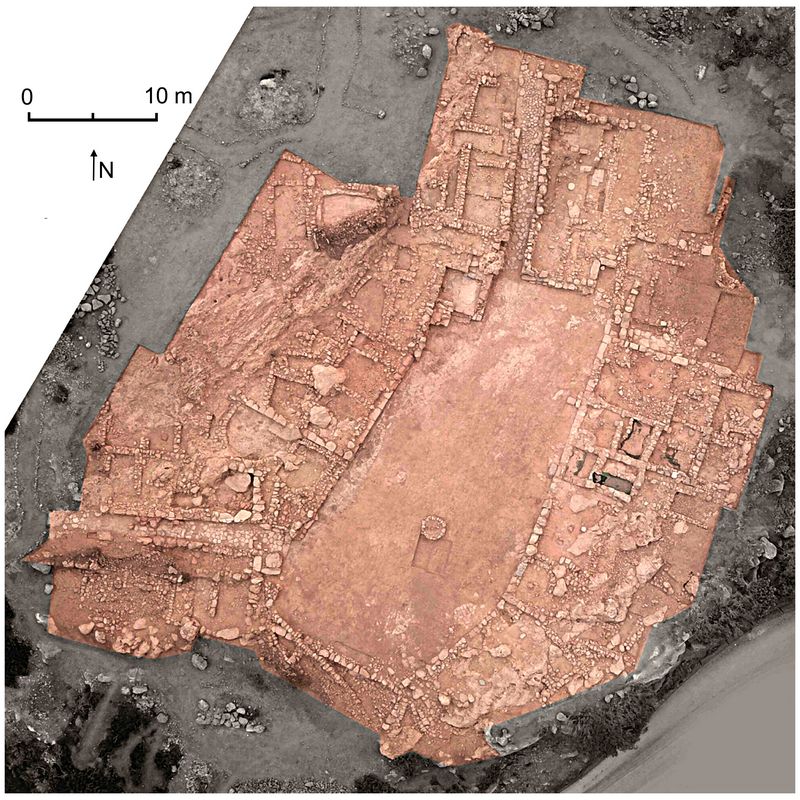

cal sampling

and FTR analysis. We also pay much attention to residue analysis. Fig.5: Aerial photo of the Sissi Ceremonial Complex at the end of the 2018 season (photo: N. Kress. The rights of the monuments depicted belong to the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports [Law 3028/2002] © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports).

All information is fixed by state-of-the art topographical equipment, which allows the data to be integrated in a GIS environment. This is helped by the use of field computers and aerial photography UAS (Phantom II). This allows an immediate visual rendering of results and use of data. In addition, a video-notebook is kept. Photogrammetric planning of architectural remains and 3-D rendering also allows proper appreciation. Wall consolidation and site presentation also take place during and after excavation, as do guided tours and public outreach.

Findings:

In detail, the 2018 grant allowed the further exploration of the large ceremonial building, known as the CCB (Court-Centered Building) during the fourth excavation season (June 25th-August 3rd, 2018). With a size of more than 1270 m² (figs.5+6), the building comprises several wings around a large trapezoidal court, 9.60 m wide to the north and 15.30 m in its center while its confirmed length is 33 m.

The court, made of plaster and pebbles, has a size of at least 450 m² and we were able to recognize two phases in its construction as well as a series of ritual installations. These comprise a kernos (a massive stone with shallow hollows, perhaps a calendar stone), a bench with hollows for depositions, a central clay fire place in the court, which may have been a fire altar, as well as a stepped platform and horns of consecration.

All suggest that the primary function of the court was ritual and ceremonial and that it formed the raison d’être for the complex which did not yield

evidence for production, storage or

administration as the larger palatial centers at Knossos, Phaistos and

Malia have.

evidence for production, storage or

administration as the larger palatial centers at Knossos, Phaistos and

Malia have. Fig.6: the paved Northern Entrance Passage arriving at the court, next to the raised room platform in the Court Centered Building (photo: N. Kress. The rights of the monuments depicted belong to the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports [Law 3028/2002] © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.)

In 2018, we were also able to excavate areas to the south, east, west and north of the court. This resulted in the discovery of several finely paved entrance passages, all leading directly into the Central Court. The finest is the one coming from the north, which arrives at the court just next to a raised room and platform (fig.6). Again, this underlines that accessibility of the court from all sides was a prime reason for its construction, stressing its communal character.

Oddly enough, some of the access passages were blocked before the abandonment of the building in Late Minoan IA. This abandonment is reflected by a few vases left behind and the presence of volcanic ash from Santorini that was found in the west wing. Is this court-centered complex a structure that can be called a ‘palace’ in Minoan terminology? i.e. do its architectural lay-out and functional organization compare positively with those of the three main palaces at Knossos, Phaistos and Malia, or does it represent another kind of (standardized?) building type?

Ongoing Plans:

Further exploration of the court and surrounding structures should allow us to draw firmer conclusions. Moreover, we are interested in learning more about the date and modalities of its abandonment and its architectural phases, which are the aims of the 2019 campaign, the last of our fieldwork activities.

Through our website (www.sarpedon.be), visitors can download images and read about the yearly progress of excavations and site consolidation. We have received several distinctions for our outreach program (Andante Archaeology Travel Award, Agios Nikolaos Tourist Award).

For more information, see:

- SISSI I = J. Driessen, I. Schoep, F. Carpentier, I. Crevecoeur, M. Devolder, F. Gaignerot-Driessen, H. Fiasse, P. Hacigüzeller, S. Jusseret, C. Langohr, Q. Letesson & A. Schmitt, Excavations at Sissi. Preliminary Report on the 2007-2008 Campaigns (Aegis 1), Presses Universitaires de Louvain 2009.

- SISSI II = J. Driessen, I. Schoep, F. Carpentier, I. Crevecoeur, M. Devolder, F. Gaignerot-Driessen, P. Hacigüzeller, V. Isaakidou, S. Jusseret, C. Langohr, Q. Letesson & A. Schmitt, Excavations at Sissi, II. Preliminary Report on the 2009-2010 Campaigns (Aegis 4), Presses Universitaires de Louvain 2011.

- SISSI III = J. Driessen, I. Schoep, M. Anastasiadou, F. Carpentier, I. Crevecoeur, S. Déderix, M. Devolder, F. Gaignerot-Driessen, S. Jusseret, C. Langohr, Q. Letesson, F. Liard, A. Schmitt, C. Tsoraki & R. Veropoulidou, Excavations at Sissi, III. Preliminary Report on the 2011 Campaign (Aegis 6), Presses Universitaires de Louvain 2013.

- Sissi IV = J. Driessen, M. Anastasiadou, I. Caloi, T. Claeys, S. Déderix, M. Devolder, S. Jusseret, C. Langohr, Q. Letesson, I. Mathioudaki, O. Mouthuy, A. Schmitt, Excavations at Sissi, IV. Preliminary Report on the 2015-2016 Campaigns (Aegis 13), Presses Universitaires de Louvain 2018.

Recent Foundation grants: general Archaeology Grants Program w/map

Copyright © 2018 Rust Family Foundation