Rust Family Foundation: Archaeology Grants Program

Exploring the Impact of the Roman Conquest on Indigenous Peoples and Settlements at Vagnari, south-east Italy

Principal Investigator: Maureen Carroll

Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield

Few Roman imperial properties have been the object of detailed and systematic archaeological investigation. The multidisciplinary research at Vagnari, the central settlement (vicus) of an imperial property in south-east Italy, is important to understand the role of such an estate in the regional and extra-regional economy of Italy and to explore the emperorís land-owning involvement in the exploitation of the environment. The project also significantly enables us to investigate the nature, origins, and social complexity of the population living here.

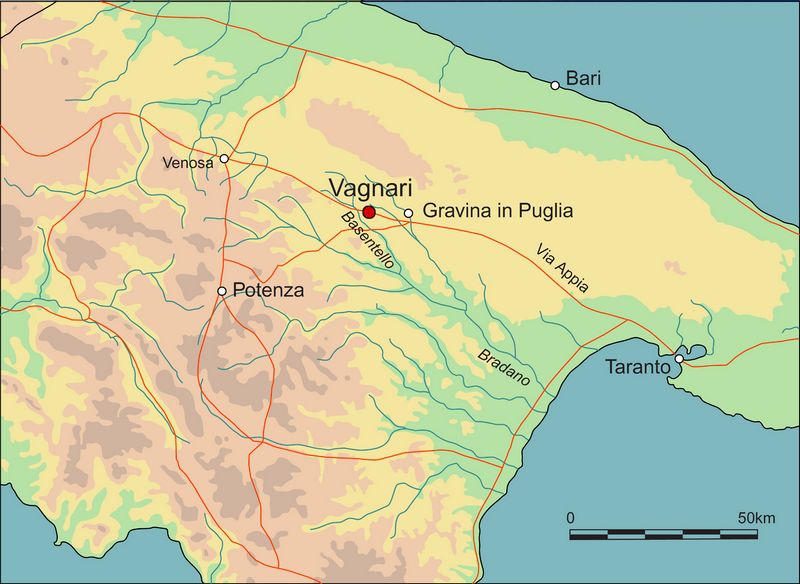

Fig.1: Location of Vagnari in southern Italy.

.

Previous Research in the region

Previous Research in the regionThe site of Vagnari was identified through geophysical prospection, survey and test-trenching conducted from 2000-2010. Since 2012, the main objectives of the archaeological project by the University of Sheffield have been to investigate the infrastructure, the economy, and the role of slave and free labour in the settlement in the Roman imperial period. Recently retrieved evidence for an older settlement of the 2nd century B.C. and for early imperial activity at Vagnari enables us also to explore the interaction between the indigenous population and the influx of groups of Roman settlers over time.

Fig.2: Students and staff excavating soil deposits, walls, and drains of the early 1st century A.D.

2017 Funded Research Project (RFF-2017-34)

Goals:

The goal of the project funded by the Rust Family Foundation was to gain an understanding of the types of ceramics in use in the last centuries B.C. and in the early Roman period at Vagnari and to identify diagnostic chronological markers of those occupation phases. We also strove to ascertain what trade networks existed and how they changed, what imported commodities might have found their way to Vagnari and how they were consumed, and to recognise patterns of food preparation over time through the ceramic record.

Methodology:

In July 2017, we conducted a study of the Roman ceramics recovered in the excavation of the Roman imperial estate at Vagnari in 2015 and 2016. The study was carried out in the offices of the Soprin

tendenza

Archeologica della Puglia in Gravina in Puglia. The work focused on

material from a settlement of the last two centuries B.C. and from a

settlement of the first four centuries A.D. at Vagnari. The pottery

was studied by Coralie Clover, MA in Museum and Artefact Studies

(Durham University). The artefact

drawings were made by Sally Cann.

tendenza

Archeologica della Puglia in Gravina in Puglia. The work focused on

material from a settlement of the last two centuries B.C. and from a

settlement of the first four centuries A.D. at Vagnari. The pottery

was studied by Coralie Clover, MA in Museum and Artefact Studies

(Durham University). The artefact

drawings were made by Sally Cann.Fig.3: Red-slip bowl dating from the 4th century A.D. (Phase III), excavated at Vagnari.

The methodology entailed quantifying the size and diversity of ceramic assemblages, determining a referenced type-series defined by form and fabric, and studying key pottery groups and stratigraphic sequences. In taking this approach, we have refined the chronological parameters for phases of activity at Vagnari and enhanced our understanding for the dating of local products and traded wares to the site. The pottery studied includes coarse cooking wares, plain wares, fine wares, storage vessels, and amphorae.

Findings:

Three distinct phases of settlement activity at Vagnari are now evident.

1. There was a resettlement of the area in the 2nd century B.C., after the Roman devastation of this and other regions in Apulia in the 3rd century B.C., with a clear break in occupation in the middle of the 1st century B.C. This activity may represent the appropriation of the area by powerful senatorial elites from Rome who grew rich by colonizing the areas defeated by Rome.

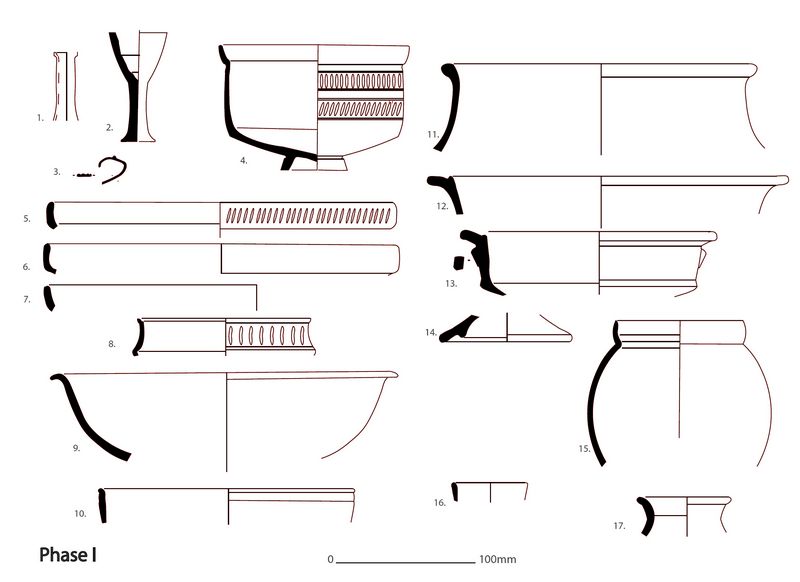

Fig.4: Pottery of the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C. (Settlement Phase I).

The pottery of the first phase (fig.4) included perfume flasks, oil lamps, plates, cups, and bowls. Most of these vessels and fabrics are widespread throughout the Greek colonies and Italic settlements of southern Italy and Sicily, but they also occur in areas around Rome. One of these cups may have been a treasured heirloom, as it dates to the 3rd century B.C. The largest group of vessels of this phase were so-called grey gloss pottery, made in southern Italy, possibly at the Greek colony at Metaponto on the south coast.

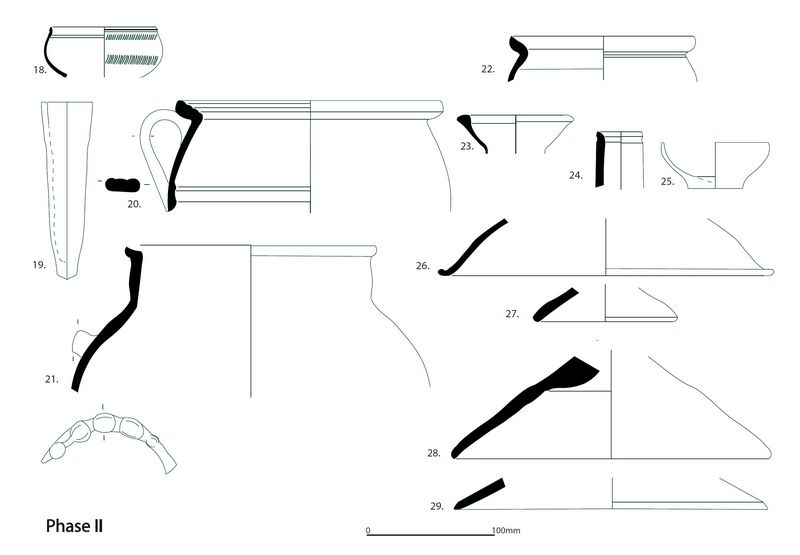

2. There was a re-establishment of the settlement with renewed building activity and occupation in the early 1st century A.D., when the Roman emperor acquired the territory as a revenue base and established the imperial village. A new range of ceramic assemblages may indicate an influx of new settlers.

This second phase at Vagnari is represented only by the contents of one pit (at this point). The dominant pottery here (fig.5) is red-slipped table wares, mainly of southern Italian production. An amphora imported from the south-eastern Mediterranean (possibly Egypt or Palestine) and coarse storage and cooking vessels are also represented. All of the pottery is considerably different from the earlier phase of the settlement, and, together with the appearance of substantial new buildings at this time, it suggests that a new population was brought in with their own material culture to create a new and expanded (imperial) settlement in the early 1st century A.D.

.

Fig.5: Pottery of the early- to-mid-1st century A.D. (Settlement Phase II).

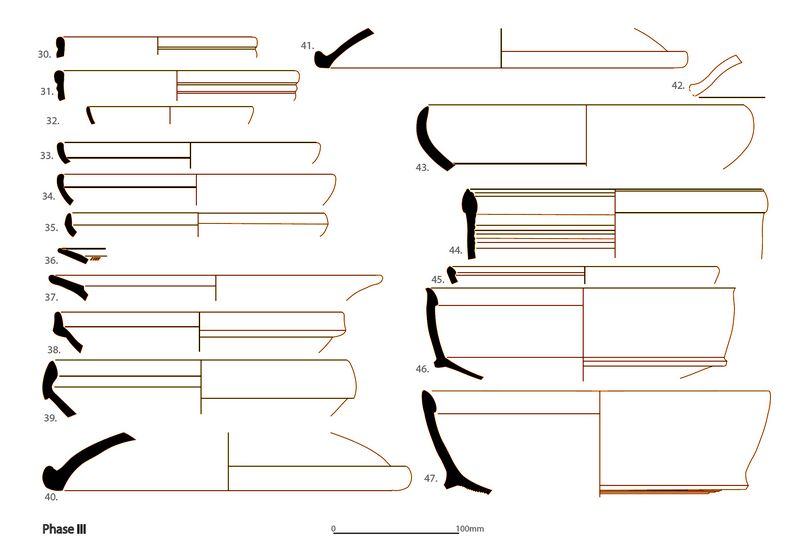

3. The last phase in the 3rd and 4th centuries A.D. represents a period of change, and perhaps decline, at Vagnari. Trade connections with North Africa are indicated by large quantities of African Red Slip ware, used as kitchen and table wares. The deposits containing this material were presumed during excavation to have been from an early phase of the Roman imperial settlement, because of their stratigraphic position. Surprisingly, however, the pottery suggests that this material stems from the destruction of the village (ca. 4th century).

The pottery (fig.6) included several cooking vessels with lids which are closely related to more northern Mediterranean and continental dietary practices, where such forms were used to cook liquid-rich stews of meat and grains (cooler climate foods); also open cooking bowls or casseroles were present which reflect a southern Mediterranean diet of drier meat and legume dishes (warmer climate foods). The North African wares, especially the African Red Slip table wares with stamped decoration, represent a widely distributed commodity throughout the Mediterranean at this time.

Fig.6: Pottery of the 3rd and 4th centuries A.D. (Settlement Phase III).

Fig.6: Pottery of the 3rd and 4th centuries A.D. (Settlement Phase III).Equally surprising was the discovery of North African pottery of the early 5th c. A.D. in the backfill of a wall robbed out for its stone, providing firm evidence that the salvaging of building materials was being carried out, probably for re-use for a new Roman settlement, no longer in imperial hands, of 5th - to 7th - century A.D. date established less than a kilometre away.

Conclusions:

With the completion of the fieldwork in 2017, we have gained valuable information on the range of ceramics in different phases of the settlement, on the use of pottery, and on the regions of origin of the wares present at Vagnari.

We have gained an understanding of the types of ceramics in use in the pre-imperial and the imperial periods at Vagnari and we can chronologically assign occupation phases. Although neighbouring archaeological sites indicate a permanent cessation in occupation in the 3rd century B.C., due to the Roman conquest and the devastating power struggles between Rome and Carthage in southern Italy, the material culture of the site shows definitively that the area around Vagnari had been resettled after the widespread upheaval of the previous century in the region.

We also have a better idea about trade networks within and beyond Italy for domestic and commercial ceramics at Vagnari, as well as some insight into culinary practices of the inhabitants at the site.

Publications:

M. Carroll (2014), Vagnari 2012: New Work in the vicus by the University of Sheffield, in A.M. Small (ed.), Beyond Vagnari. New Themes in the Study of Roman South Italy. Bari, 79-88

M. Carroll (2016), Vagnari. Is this the winery of Romeís greatest landowner?, Current World Archaeology 76: 30-33

M. Carroll and T.L. Prowse (2016), Research at the Roman Imperial Estate at Vagnari, Puglia (Comune di Gravina in Puglia, Provincia di Bari, Regione Puglia), Papers of the British School at Rome 84: 333-336

M. Carroll and T.L. Prowse (2017), Research at the Roman Imperial Estate at Vagnari, Puglia (Comune di Gravina in Puglia, Provincia di Bari, Regione Puglia), Papers of the British School at Rome 85: 330-334

Vagnari Vicus Archaeological Project website:

https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/archaeology/research/vagnari

Recent Foundation grants: general Archaeology Grants Program w/map

Copyright © 2018 Rust Family Foundation