Rust Family Foundation: Archaeology Grants Program

The Prastio Village Cemetery Project [Cyprus]

Principal Investigators:

Dr. Tate S. Paulette, Department of History, North Carolina State University

Dr. Kathryn M. Grossman, Department of Anthropology, North Carolina State University

The Prastio Village Cemetery Project was conceived as the first stage of a larger research program that aims to provide a backstory for the process of urbanization in Bronze Age Cyprus by focusing on the immediately pre-urban phase on the island.

The emergence of cities in Cyprus during the Late Bronze Age (c. 1650–1050 BC) is typically understood to have been driven by the copper trade and, specifically, by the rapid concentration of wealth and power within the hands of a small class of elites who were able to exploit a sudden demand for Cypriot copper. Our project is looking for evidence of incipient elites and associated centralized institutions during the preceding Early and Middle Bronze Age (2400-1650 BC). A main focus is on the degree to which control of economic activities – by institutions, aggrandizing elites, or powerful households – might have preceded the large-scale exploitation of the island’s copper resources.

Fig.1: Map of Cyprus showing location of Prastio (Athena Review Image Archive)

Previous Research at the Site

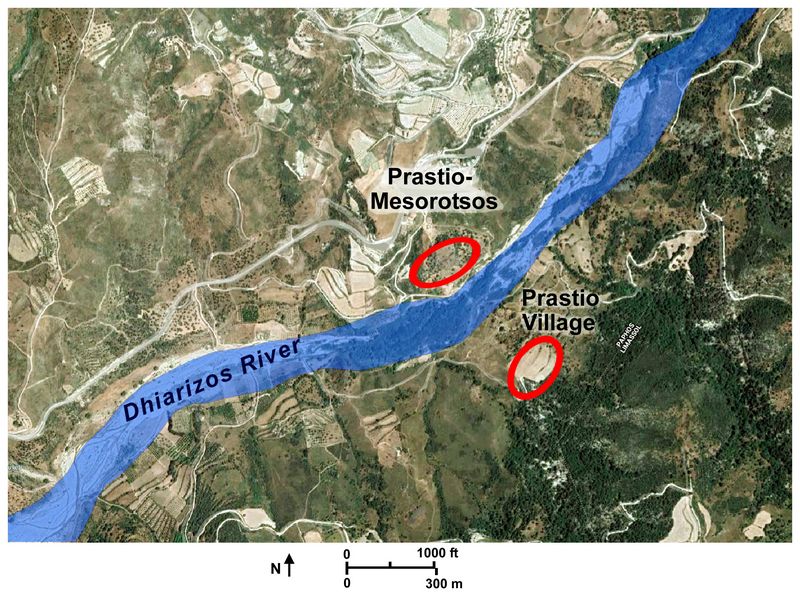

A brief survey at Prastio Village had been conducted by the team working at Prastio-Mesorotsos (a long-lived settlement site across the river from Prastio Village), under the direction of Dr. Andrew McCarthy and Dr. Lisa Graham. The Prastio team had carried out a small-scale, unsystematic survey of the fields near Prastio Village, which had yielded some Middle Bronze Age sherds. In 2012, the Prastio-Mesorotsos project also conducted a small electromagnetic resistivity survey to see if the sherd findspots correlated with any subsurface features. The r

esistivity was largely inconclusive, revealing little subsurface architecture,

leading the team to suspect that the Middle Bronze Age sherds derived

not from settlement contexts but from rock-cut tombs.

esistivity was largely inconclusive, revealing little subsurface architecture,

leading the team to suspect that the Middle Bronze Age sherds derived

not from settlement contexts but from rock-cut tombs.Fig.2: Satellite image showing location of Prastio Village and Prastio-Mesorotsos (Google Images).

The dating of prehistoric Bronze Age sites on Cyprus has been based primarily on rough, relative ceramic chronologies derived largely from funerary contexts, rather than settlements. The lack of connection between funerary and settlement ceramic assemblages is well known among Cypriot archaeologists, but pre-urban sites containing both settlements and cemeteries have rarely been excavated. Given the presence of an Early–Middle Cypriot settlement at Prastio-Mesorotsos and the possibility of a contemporary cemetery across the river at Prastio Village, further study of Prastio Village appeared to offer an excellent chance to establish a correlation between settlement- and cemetery-derived ceramic chronologies and, therefore, a chance to provide a more complete and more fine-grained analysis of socio-economic developments during the buildup to urbanization and state formation.

Funded Research Project (RFF-2016-17)

Goals:

In July and August of 2016, we initiated a program of systematic survey and surface collection at Prastio Village, to determine whether the Prastio Village site would be an appropriate location for a larger scale excavation program that would serve as the first stage in our broader effort to study urban origins on the island. We deployed two further geophysical survey techniques (Ground Penetrating Radar and magnetometry) to complement the earlier resistivity study.

This project included four subgoals:

1. Conduct an intensive pedestrian survey and surface collection at the site of Prastio Village.

2. Conduct a subsurface geophysical survey using ground penetrating radar and

magnetometry at the site of Prastio Village.

3. Conduct preliminary ceramic analysis to determine if Early and Middle Bronze Age sherds derive from mortuary or non-mortuary contexts.

4. Train undergraduate students in survey, geophysics, and post-recovery analysis. Six undergraduate students from MIT and Wellesley accompanied us to Prastio Village to learn archaeological field techniques.

A fifth goal, to conduct test excavations to ground truth any significant findings from the geophysical survey, was not pursued, given the paucity of geophysical evidence for Bronze Age tombs at the Prastio Village site and the limited Bronze Age ceramic assemblage.

Methods and Results:

Surface survey

We conducted an intensive surface collection and geophysical survey at the site of Prastio Village (see figs.1 and 2). Over the course of two weeks, our field school students recovered 1575 sherds and objects from 752 collection units. The survey used a combination of systematic and non-systematic sampling procedures to collect archaeological data in the fields above the extant remains of the abandoned Prastio Village. This combination enabled us to maximize the area covered, and at the same time, to compare the results of both survey types in order to evaluate potential collection bias in the early unsystematic survey conducted by the Prastio-Mesorotsos team. The fiel

ds surveyed have been impacted by

modern terracing and plowing, not for the purpose of cultivation, but

as a way to prevent erosion on a treeless slope. This modern activity

has undoubtedly impacted some of the remains.

ds surveyed have been impacted by

modern terracing and plowing, not for the purpose of cultivation, but

as a way to prevent erosion on a treeless slope. This modern activity

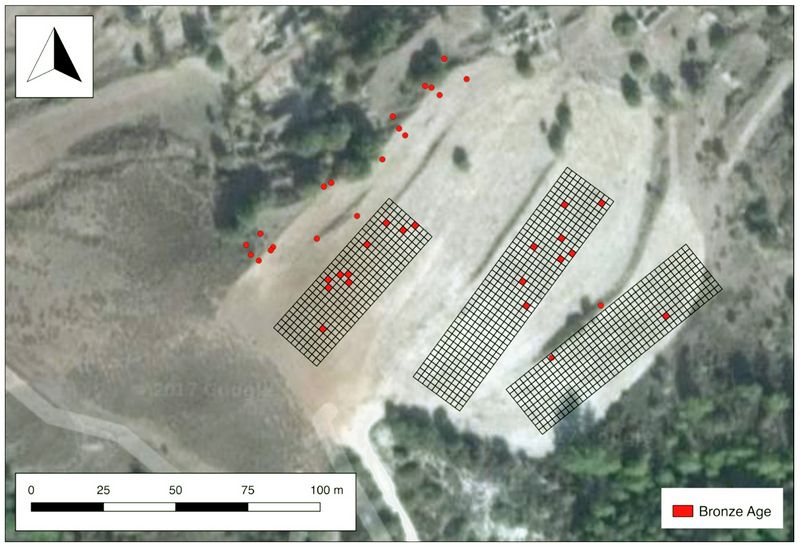

has undoubtedly impacted some of the remains.Fig.3: Results of surface collection: distribution of Bronze Age sherds.

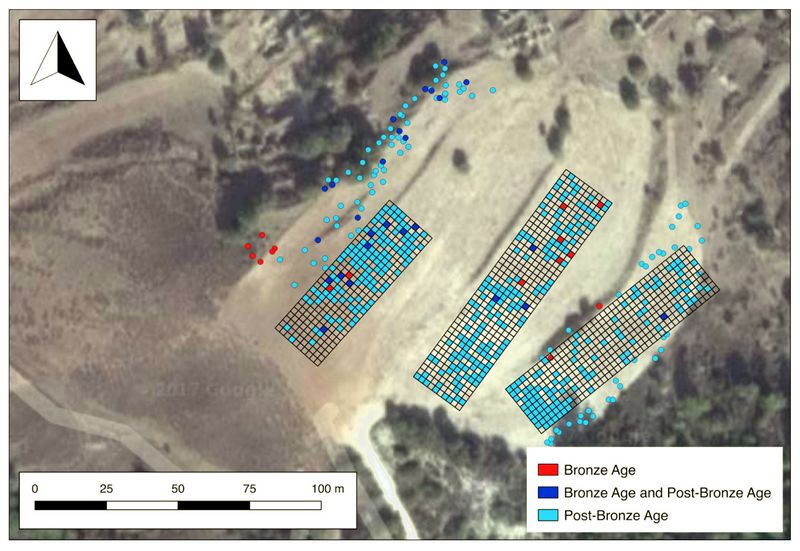

The systematic survey area included a series of three rectangular collection grids located in the terraced fields (indicated in figs.3, 4, and 5), subdivided into 2x2 m squares in which total surface artifact collection was attempted. In the parallel, unsystematic survey, surface remains were collected from outside of the gridded areas, again attempting total collection within 2x2 m squares, but without relying on transects or grids. Fig.3 shows occurrences of Bronze Age ceramics (all from the Early or Middle Bronze Age, none from the Late Bronze Age) from these collection areas indicated in red and post-Bronze Age ceramics indicated in blue.

Overall sherd density in all collection areas was generally low, with no single collection unit yielding more than 12 artifacts, and most yielding 1 or 2. This low sherd density was surprising, given the proximity of Prastio Village where larger ceramic depositsof the Venetian or modern periods might be expected. Following collection, sherds were washed by the field school students, analyzed by

Dr. Lisa Graham, and recorded

with diagnostic pieces photographed. Very few non-ceramic

artifacts were recovered, including only 66 pieces of chipped stone, 3

pieces of glass, 5 pieces of ground stone, and no organic remains.

Dr. Lisa Graham, and recorded

with diagnostic pieces photographed. Very few non-ceramic

artifacts were recovered, including only 66 pieces of chipped stone, 3

pieces of glass, 5 pieces of ground stone, and no organic remains.Fig.4: Results of surface collection: distribution of Hellenistic/Roman sherds and roof tiles.

Unexpectedly, the vast majority of sherds found in these fields was neither Bronze Age nor Medieval or later, but Hellenistic and/or Roman in date. The yellow dots on fig.4 indicate diagnostic Hellenistic sherds, although there may be more among the sherds that were too eroded to confidently identify. Certainly, some of the sherds that were identified as “Hellenistic/Roman” based solely on fabric are Hellenistic remains. The artefacts recovered in the surface collection also included roof tiles, which indicates that structures were located nearby, lending credence to the idea that the subsurface anomalies identified in the geophysics (see below) could be the location of Hellenistic structures, possibly surrounded by a terrace or ditch. Only 40 sherds, out of the 1575, could be dated to the Bronze Age. It is possible that Bronze Age remains (tombs or otherwise) remain deeply buried, but as discussed below, Gound Penetr

ating Radar results does not support that

supposition.

ating Radar results does not support that

supposition.Fig.5: Results of surface collection, showing all collection units from which artifacts (from all periods) were recovered. Note that even with total collection in the systematic survey grids, many collection units yielded no remains.

Geophysical survey:

Both ground penetrating radar and magnetometry surveys were conducted at the site by partnering with the Cyprus Institute’s Science and Technology in Archaeology Research Center (STARC). The geophysical survey of subsurface remains produced some intriguing evidence for large scale earthworks, and possibly some Hellenistic structures. Ms. Markussen, assisted by the students, c

onducted

geophysical survey using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and

magnetometry within the gridded areas of the systematic surface

collection, in an attempt to correlate surface finds and subsurface

features.

onducted

geophysical survey using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and

magnetometry within the gridded areas of the systematic surface

collection, in an attempt to correlate surface finds and subsurface

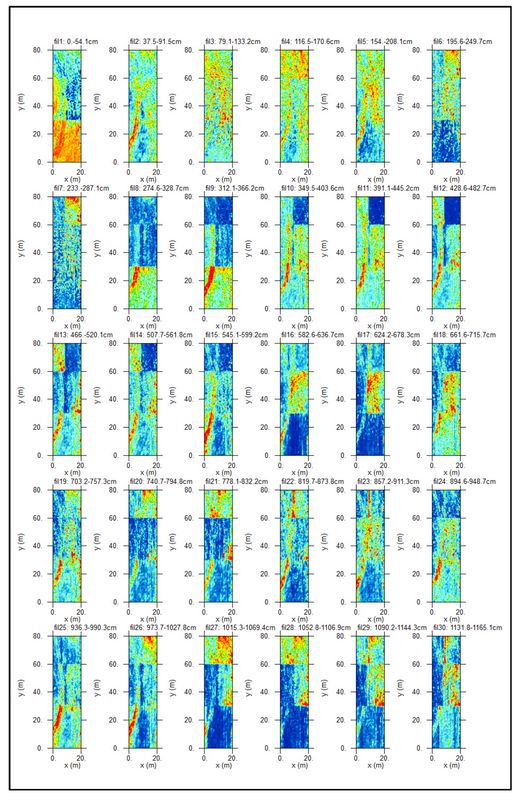

features. Fig.6: GPR slices for Prastio Village, central grid. Note the curvilinear feature visible in most slices.

GPR was conducted in all three survey grids in the Prastio Village plots. GPR, which can detect buried subsurface remains at substantial depths, but generally at a coarser resolution, yields the “sliced” images of subsurface remains at various depths shown in fig. 6. The key observation from the slices presented in fig.6 (from the central grid, the most well-defined data) is the recurring curvilinear feature shown in most of the slices. This could be a previous field boundary or terrace wall or alternatively a filled-in ditch of some sort. The latter interpretation would correspond to a ditch that was found in the course of excavations in a Hellenistic context on the opposite bank of the river at Prastio-Mesorotsos. It is also worth pointing out that the modern terracing operations in the Prastio Village fields seem not to have heavily impacted these subsurface remains, which are visible in slices both close to the surface and at significant depth.

Also conducted was a magnetometry survey, which can usually detect subsurface features at a higher resolution than GPR, but whose output is a single image showing all features from the surface down to approximately 1.5m below the surface, rather than multiple images at multiple depths.

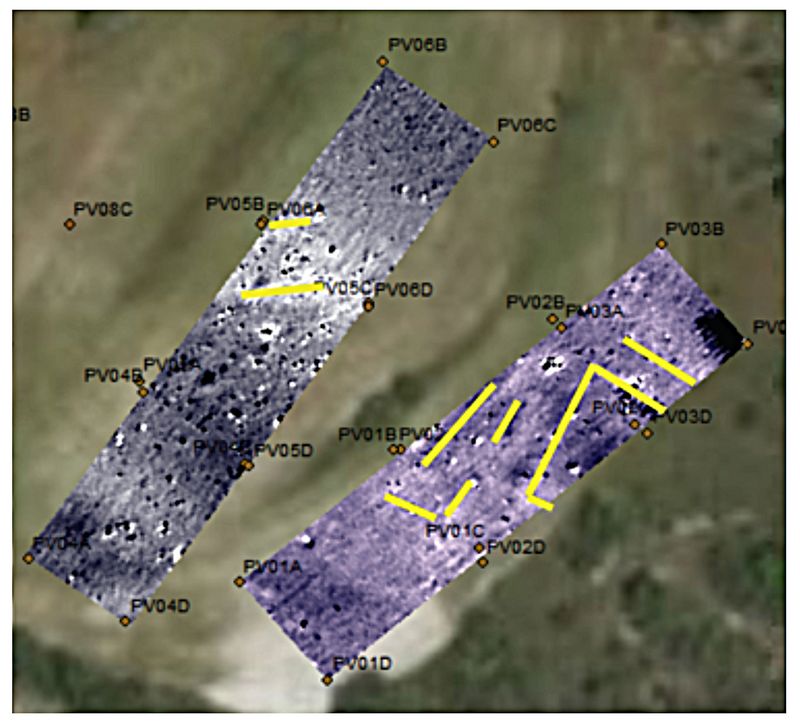

Fig.7: Closeup image of magnetometry results, with linear anomalies indicated in yellow.

The magnetometry was conducted only on the central and eastern two gridded areas, resulting in overlapping geophysical methods in those two grids. The magnetometry revealed some clear linear subsurface features that did not align to the plough lines, nor to the slope of the field (fig.7). These anomalies occurred in the area of the fields where very few prehistoric sherds were found, and it seems likely that they represent Hellenistic period structures.

Ceramic analysis:

While the original goal was to conduct preliminary ceramic analysis to determine if Early and Middle Bronze Age sherds derive from mortuary or non-mortuary contexts, an absence of tomb evidence from the survey combined with a lack of many Bronze Age sherds obviated such correlations. For the overall ceramic sample,Dr. Lisa Graham and Dr. Andrew McCarthy completed a study of the ceramic remains from Prastio Village in the fall of 2017, and Dr. Tate Paulette, assisted by one of our students, mapped the sherds and geophysical results using ArcGIS shortly thereafter.

Conclusions:

Our work at Prastio Village has produced some important new insights about the nature of Hellenistic settlement patterns on Cyprus, and it has provided new research questions for the archaeology of the first millennium BC on the island. Excavation and surface collection at the site of Prastio-Mesorotsos, on the western bank of the Dhiarizos River, has revealed evidence of occupation dating from the Neolithic to modern times. The archaeological traces from the Hellenistic and Roman periods, however, are some of the sparsest represented in the stratigraphic sequence, likely due to ploughing activities and Medieval and later construction. Despite that scarcity, the Prastio-Mesorotsos team has developed a good understanding of the size and type of community that occupied the site during the Hellenistic period through surface finds and spatial data.

The 2016 geophysical prospection and surface collection from the Prastio Village fields –which sit only a few hundred meters from Prastio-Mesorotsos, on the opposite (east) bank of the Dhiarizos River – produced an assemblage of Hellenistic finds comparable to those found on the west bank. These unexpected results show that this rural site was much larger than previously reported for the Hellenistic period and that this location was quite possibly a river-crossing point on one of the main routes from the resource-rich Troodos Mountains to the coastal city of Paphos at this time.

In the primary research focus of the Bronze Age, meanwhile, Prastio Village yielded disappointingly sparse remains from that period. GPR, which we had hoped would yield some evidence of buried Bronze Age rock-cut tombs, showed nothing of the sort. The project focus has, therefore, shifted to the site of Makounta-Voules, located just north of the modern town of Polis. This site has proven much more conducive to our research goals than Prastio Village.

Ongoing plans:

Makounta-Voules (known also in the academic literature as Makounta- Mersinoudhia) has long been recognized as an important Early and Middle Bronze Age site, although it had been only cursorily surveyed and never excavated. The site is located in the only region of the island where copper ore deposits are found close to the coast, just north of the modern town of Polis (fig.1). As such, the site of Makounta-Voules is well-situated for research into pre-urban developments in the Early and Middle Bronze Age on Cyprus, especially the relationship between early metallurgy and increasing social complexity.

In the summer of 2017, we conducted geophysical survey, surface collection, and section cleaning at Makounta. Our results indicate that the site was indeed a large settlement (about 7-10 ha) during the Chalcolithic period, Early Bronze Age, and Middle Bronze Age. Our section cleaning and ground penetrating radar results suggest as much as 2-3 meters of stratified remains in some areas. We also recovered 50 pieces of copper slag, and conducted a magnetometry survey (alongside GPR), which revealed highly magnetic subsurface remains that we suspect might be a metalworking area or buried slag heap.

.

Recent Foundation grants: general Archaeology Grants Program w/map

Copyright © 2020 Rust Family Foundation